Part 2 of the History of the British Infantry Shako

By 1812, the stovepipe shako had become the ugly stepchild. Britain’s contact with other European armies, both allies and enemies, highlighted the lacklustre visual appeal of the cap. Other nations had caps festooned with cords and tassels and seemed to dramatize the height of the soldier to greater advantage. In the final analysis, Britain adopted a cap closely patterned after the Portuguese “barretina” design. Ironically, at the same time the English were adding cords to their headwear, the French were abolishing them. As usual, no improvement in protection to the head was made by the design change.

Figure 1, Portuguese Caçador. Painting by Herbert Knötel

Figure 2, Portuguese Infantry officer. Painting by Herbert Knötel.

The new British cap retained several features from the old stovepipe design. The body of the hat was still made from stiffened blocked wool felt. Inside, the linen cap bag was stitched at the edge to the thin leather band that transitioned from the outside to the inside of the cap at the bottom edge. The company affiliation was still denoted by the coloured worsted tufts: white over red for Battalion companies, green for the Light company and white for the Grenadier company. At the base of the tuft there was still the black tooled leather Hanoverian cockade with regimental button. However, the placement of the tuft and cockade had been moved to the left side of the hat to make way for the false front. The body of the new design was about six and one half inches tall, but across the front of the cap was an eight and a quarter inch high tombstone shaped piece of felt. It was bound in black worsted tape and bore a brass plate in the shape of a crowned baroque shield. On the shield was the regimental number or name of the unit. Running from the base of the plume across the front of the cap under the plate and terminating on the right side were worsted cords. Grenadiers and Battalion men had white cords, but Light companies often preferred green. The Light companies in 1814 were ordered to wear a bugle badge and regimental number in place of the baroque plate.

Figure 3, Belgic shako with “universal” or un-numbered plate. Photo by Peter Twist

Figure 4, Royal Scots Light Company. Photo by Brad Stott

Regimentally marked plates were the norm for this new headwear and a great many of the designs are known.

Figure 5, Plate of the 4th Regiment. Photos by Peter Twist

Figure 6, Plate of the DeMeuron Regiment. Photos by Peter Twist

Figure 7, Plates of the 33rd Regiment. Photos by Peter Twist

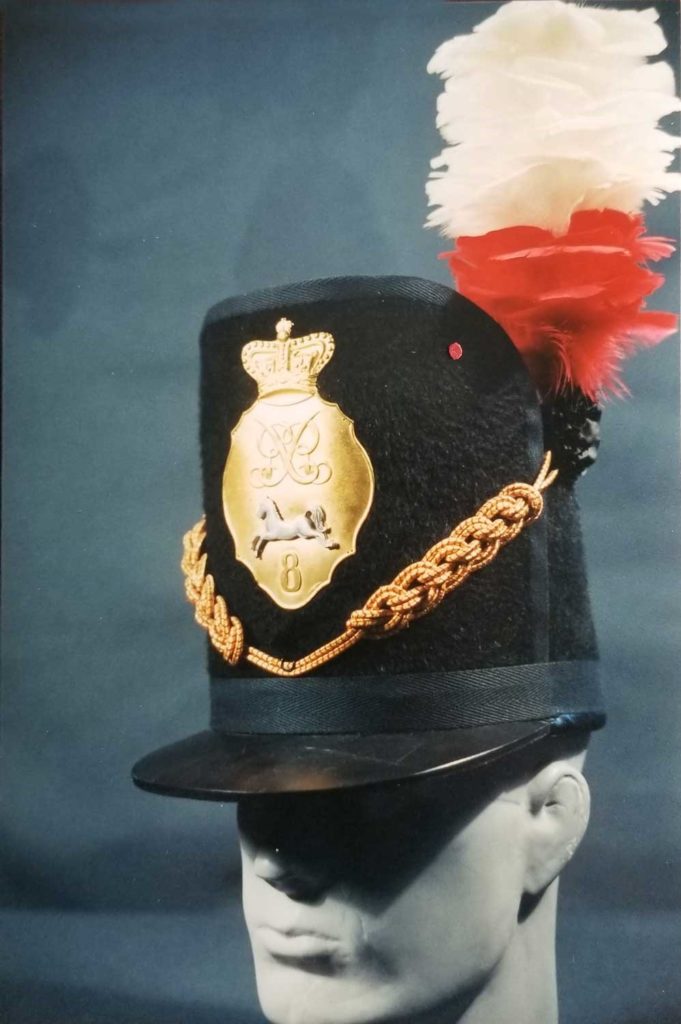

For the first time, regimental officers wore the same shako design as the men. Officer’s caps were made in beaver felt, bound in black silk ribbon, and featured gilded plates (often incorporating silver applied badges) with black silk cockades and six inch tall feather plumes in company colours. The square sectioned cap cords were mixed red and gold with bullion tassels. In 1814, Light company officers followed the same distinctions as their men.

Figure 8, Officer’s Belgic shako, King’s Regiment. Photo by Peter Twist

Figure 9, Officer’s Belgic shako, King’s Regiment. Photo by Peter Twist

Figure 10, Officer’s Belgic shako, King’s Regiment. Photo by Peter Twist

Once again, the Royal Artillery followed the practice of the army and adopted the same model of cap. They retained the white tufts but made the cords yellow, one of the distinctive colours of the Board of Ordinance, to make their headwear distinctive from that of the infantry. The cap plate was also a crowned baroque shield displaying the image of a mortar.

The Belgic shako proved to be a very short-lived design. It was replaced by a totally new style in 1816. Due to the two year life expectancy of shakos, there were some regiments that still hadn’t received the 1812 model by the time of Waterloo. The 28th Foot was known to still be wearing the stovepipe with the plate cut apart to make a unique design. There is also some belief that the Rifles and Light Infantry regiments eventually wore the Belgic cap, but the date of changeover is unclear.